Innovation - For Society, For Sustainability

“If I could draw a picture for you, I would draw you a picture of an hourglass. The sand would run from one glass to the other, but instead of sand flowing through it would be the garbage of our environment: industries, planes, chemical and … as it flowed through the narrow part of the glass, there would be symbols of our educated changed society. As it flowed through, all that garbage would turn to green trees, fresh water, children with full bellies and smiling faces, and families sitting around the supper table discussing their future. ”

What is Innovation and why does it matter for sustainability?

I am famous among my colleagues for this common refrain—that we do not need new technologies to address today’s various social and ecological challenges. However, that does not mean that we do not desperately need innovators and innovations to achieve a more sustainable and just society, because no doubt, the parameters of the human, anthropocene problématique are unprecendented.

Historian Arnold Toynbee famously remarked that civilization is a movement, not a condition. The same, I believe, is true for sustainability—it is not a finish line for social and environmental progress, but an entirely different way of seeing, living with, and adapting, with the world around us. And what is the engine that drives this movement? I believe it is the creativity and penchant for innovation and flexibility that has characterized our species for millennia.

Innovation, in its most basic sense, describes a deviation from the standard, institutionalized ways of doing things. That being said, innovation is neither prosaic nor mundane. New kinds of smart phone or self-driving tractors are not, on their own, innovations. These are merely gradual improvements or refinements of the status quo. True innovations do more than just replace old things. They destabilize the existing ways of doing things in favor of some new paradigm. True innovations are driven by social movement, by a visceral collective need for new tools to achieve people’s emerging vision for society.

Some innovations, what many call social innovations, are special not only do they provide the tools for people to realize a better future, but also because they “feed back” to create positive social change. Social innovations accelerate social change because they not only change how we do things, but they also change how we relate to one another through those activities. Social innovations democratize; they devolve and distribute power and wealth; they are actively anti-racist and anti-colonial.

WhEN innovations Succeed

Good ideas might not come around every day, but when they do come around, they aren’t guaranteed to catch on. Decades of scientific study have been invested in answering the question of why, and how, innovations spread (or become forgotten). The most famous theory comes from Everett Rogers’ 1962 book, “The Diffusion of Innovations.” Though more than a half-century old, Roger’s general theory remains widely accepted. In brief, Rogers proposed five phases in the adoption of an innovation over time—innovators, early adopters, majority adopters, late adopters, and laggards. He and believed that social factors, the rate of adoption, and communication channels were key factors in whether or not an innovation would take hold.

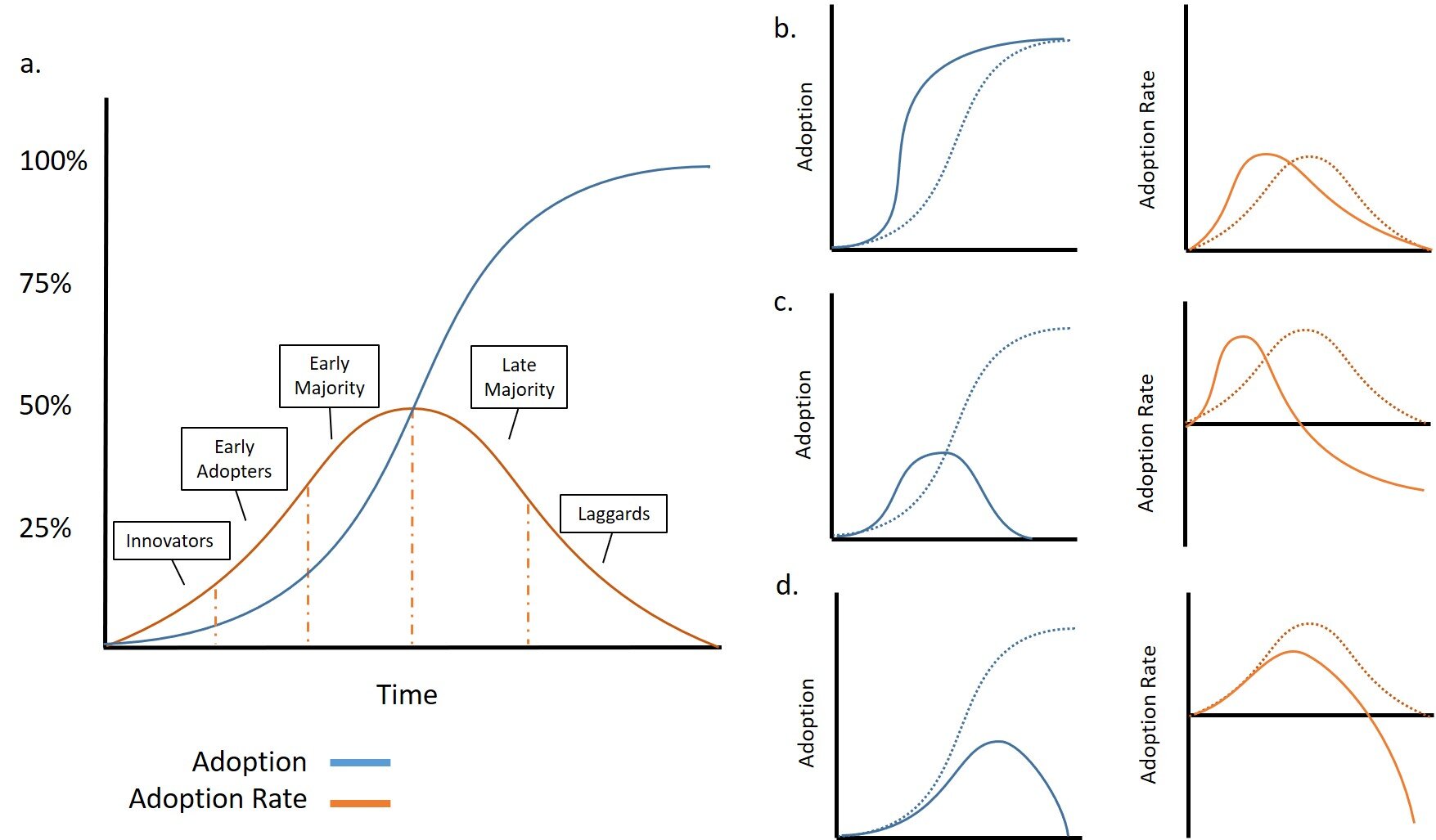

Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation theory. a) successful adoption of the innovation in five phases (orange), superimposed with the total adoption rate’ b) an example of a rapid adoption, perhaps subsidized to reach an early majority very quickly; c) failed adoption after early enthusiasm, perhaps because of poor communication; d) failed adoption, perhaps because of competition from a superior successful innovation.

Tipping Points

Also key to Rogers’ theory is the notion of critical mass, or “tipping point” after which, ultimately, the total diffusion of an innovation is likely. Above, the tipping point is the inflection point between the early and late majority in the sigmoid curve of adoption. Tipping points essentially refer to thresholds—the point in time during change at which the forces of innovation pushing for some new state outweigh the conservative forces working to maintain the status quo. To put this in the terms of resilience, the tipping point is the point at which the forces of disturbance or transformation push the current system overcome the resilience of that system.

Innovation and Regimes

Another major theory regarding innovation, one much more contested than Rogers but as informative is socio-technical transitions theory, or what I call the regime theory of innovation. This comes primarily from the work of Frank W. Geels. Geels’ theory also focuses on the forces that conserve existing ways of doing things, what he referred to a socio-technical regimes, and the circumstances that empower agents of change to create and expand new niches of innovation into the mainstream. Geels’ theory excels for its explicit incorporation of deep structural and societal factors, such as history, path dependence, and the influence of large firms and culture. Socio-technical regime theory also incorporates the notion of slow and fast changes, which refers to the fact that individual agents can affect change much more quickly than can large firms or institutions, though changes initiated by the latter face fewer challenges to becoming lasting. Evident in this work, too, is an implicit acknowledgment of Rogers’ proposed sigmoid nature of the adoption of innovations.

NO MORE HEROES

For generations, western culture has believed in a flawed theory of change—the great (white) man theory of change. We have a collective hero complex, an in-built assumption that big problems are only solved when someone with extraordinary gifts comes along. While there are, to be sure, extraordinary people in our history, men and women, real and transformative change doesn’t happen because individual heroes make that change for us, but because people, en masse, have been lifted up and empowered to create change collectively.

And really, that’s the only way to ensure change that is equitable and just. It must come from a context of democratic deliberation and collaboration, not one of power and social engineering. We don’t, in other worlds, need to wait for people like Elon Musk to generate the innovations we need to transform our world. Down that road lies only more disappointment, more colonialism, more latent white supremacy. No, we need a legion of innovators working on big problems together.

You can hear more about my thoughts on a post-heroic theory of change in my TEDx talk below.